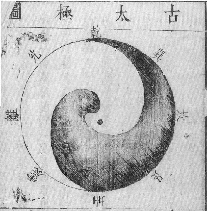

Sometimes mispronounced “tai-ch’i,” Taiji quan 太極拳 (T’ai-chi ch’üan) literally means “Supreme Ultimate Boxing.” Here Taiji 太極 (lit., “great ridgepole”) refers to yin-yang interaction, so that the modern Taiji diagram is the Yin-yang symbol. This diagram is sometimes used as a symbol for Chinese martial arts by martial artists and sometimes as a symbol for Daoism by Daoists. These two are often conflated in the popular understanding of “Daoism.” Historically speaking, it is unclear when the modern Taiji diagram was created (cf. the Taiji tu 太極 圖 by Zhou Dunyi 周敦頤 [1017-1073]) and when Chinese Daoists began using it. In earlier Daoist history, the “yin-yang symbol” referred to the image of a tiger and dragon. The modern version may have been adopted by Daoists to compete with the symbolic representations of other religious traditions: the cross of Christianity, swastika of Buddhism, crescent moon of Islam, Star of David of Judaism, and so forth.

Diagram of Taiji by Zhang Huang 章潢 (1527-1608)

Taiji refers to the cosmogonic moment when the Dao, through a spontaneous, impersonal process of self-unfolding, moved from Wuji 無極 (Primordial Undifferentiation) to Taiji, the manifest universe based on yin-yang interaction. Taiji quan is thus a form of martial arts based on yin and yang differentiation.

Taiji quan is part of the so-called Chinese internal martial arts (neijia 内家), with the other two forms being Bagua zhang 八卦掌 (Pa-kua chang; Eight Trigram Palm) and Xingyi quan 形意拳 (Hsing-i ch’üan; Form-Intent Boxing). Historically speaking, Taiji quan is a non-religious martial arts practice. The original form of Taiji quan, Chen 陳 style, was most likely created in the early seventeenth century, possibly by Chen Wangting 陳王廷 (1600-1680). The creation of Taiji quan occurred in the famous “Chen family village,” located in present-day Wen county of Henan province. It may have been formed as a nativist response to the perceived atrophy and weakness of Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasty court culture. In this way, it would have been part of a national-upbuilding movement to combat the occupation and suppression of the native population by foreign colonist powers.

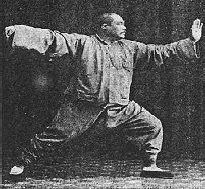

There are five primary “family styles,” including Chen, Yang 楊 (founded by Yang Luchan 楊露禪 [1799-1872]), Wu 武-Hao 郝 (founded by Wu Yuxiang 武禹襄 [1813-1880]), Wu 吳 (founded by Wu Quanyou 吳全佑 [1834-1902] and Wu Jianquan 吳鑑泉 [1870-1942]), and Sun 孫 (founded by Sun Lutang [1861-1932]).

Yang Chengfu 楊澄甫 (1883-1936) in “Single Whip”

Yang style derived from Chen style. Both the Wu-Hao style and Wu style derived from Yang style. Sun style derived from Wu-Hao style. Each has its distinguishing characteristics in postural alignment and form. There are also some very recent forms, variously identified as “ancient” (gu 古), “Daoist” (daojia 道家), “primordial original” (hunyuan 混元), and so forth.

In origin and content, Taiji quan thus is not a Daoist practice. The earliest form originates as a martial art with the (non-Daoist) Chen family most likely in the early seventeenth century. Its emphasis on yin-yang is not Daoist, but rather part of what is best understood as “traditional Chinese cosmology.” Historically speaking, that cosmology was systematized by the Cosmologist School (yinyang jia 陰陽家) of the Warring States period (480-222 BCE) under the direction of Zou Yan 鄒衍 (Tsou Yen; 305-240 BCE). It was eventually incorporated into both Chinese medical traditions and classical Daoism.

The matter is complicated by the mythological account of the origins of Taiji quan with the pseudo-historical Zhang Sanfeng 張三丰 (ca. 14th c.?) and Wudang shan 武當山 (Mount Wudang; near Shiyan, Hubei). Taiji quan is, in turn, sometimes misidentified as Wudang quan 武當拳 (Wudang Boxing). Although yet to receive a thorough academic study, preliminary historical research suggests that this mythology developed in three stages, culminating in the conflation of Zhang Sanfeng, Wudang shan, and Taiji quan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Under that fictitious history, Zhang Sanfeng, an immortal associated with Wudang, created the internal martial arts, which were eventually separated into the three neijia forms mentioned above. It is unclear when the specific forms of Wudang martial arts developed, but it may have occurred as late as the twentieth century. Legends surrounding the “Daoist origins” of Taiji quan may be compared to a parallel mythology concerning the association of certain Gongfu 功夫 (Kung Fu) systems with Shaolin si 少林寺 (Shaolin Monastery; Songshan 嵩山, Henan) and Bodhidharma (ca. 5th c. CE?).

In the modern world, there are a variety of Taiji quan forms that are identified as “Daoist.” The most well-known are those associated with Mount Wudang, which are referred to as “Wudang style.” In addition to being practiced and taught by Daoists at Mount Wudang, these forms, at least in name, have spread throughout the modern world. Practitioners, whether mainland Chinese Daoists or Western disciples, are most likely to perpetuate the mythological account of Taiji quan’s origins. Some self-identified Wudang centers include the Academy of Wudang Taoist Wushu Arts, US Wudang Association, Wudang dao, Wudang Taoist Kung Fu Academy, and Wudang Research Association. Many of these and similar groups cater to a Western clientele, with the primary motivation of making money. They are most likely to essentialize or reduce Daoist practice to martial arts training. They have gained cultural capital from popular cultural representations, such as in the film Wohu canglong 臥虎藏龍 (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon; released in 2000).

One also finds the more recent “Taoist Tai Chi” created by Moy Lin-shin (Mei Lianxian 梅連羡; 1931-1998), a Hong Kong immigrant to Canada. Apart from yin-yang cosmology and its emphasis on “being soft,” and possibly Taiji quan’s mythological Daoist associations, it is difficult to determine what led Moy to categorize the practice as such. So-called “Taoist Tai Chi” is now widespread throughout the modern world as disseminated by the International Taoist Tai Chi Society (Guoji daojia taiji quan she 國際道家太極拳社).

In the context of contemporary American society, many Taiji quan teachers have been misidentified as Daoists and/or given a post-mortem Daoist pedigree.

So, what must be understood is that Taiji quan, in contrast to popular constructions, is not Daoist in origin or in content. Practicing this martial art does not make one a Daoist. At the same time, it cannot be denied that many mainland Chinese Daoists practice Taiji quan. This includes lineage-based Wudang forms, however recent their provenance may be. When practiced by Daoists, especially Quanzhen monastics, the martial applications of Taiji quan tend to deemphasized, while the meditative and health-preserving and life-extension dimensions are highlighted. A stronger emphasis is also placed on Daoist subtle anatomy and physiology, including qi circulation. In addition, some Daoists apply certain Daoist principles, especially those derived from classical Daoist texts, to transform Taiji quan into a “Daoist practice.”

Further Reading: “A Taoist Immortal of the Ming Dynasty: Chang San-feng”/Anna Seidel; Beyond the Closed Door/Arieh Lev Breslow; “Chronology of Daoist History”/Louis Komjathy; Daoist Identity/Livia Kohn and Harold Roth (eds.); Daoism in China/Wang Yi’e; “Ignorance, Legend, and Taijiquan”/Stanley Henning; Investigations into the Authenticity of the Chang San-feng ch’uan-chi/Wong Shiu Hon; Lost T’ai-chi Classics of the Late Ch’ing Dynasty/Douglas Wile; “Models of Daoist Practice and Attainment”/Louis Komjathy; Nei Jia Quan/Jess O’Brien; “Qigong in America”/Louis Komjathy; “Periodization of Daoist History”/Louis Komjathy; T’ai Chi’s Ancestors/Douglas Wile; “Taijiquan and Daoism: From Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion”/Douglas Wile; “The Dao of America”/Elijah Siegler; The Essence and Applications of Taijiquan/Louis Swaim; The Shaolin Monastery/Meir Shahar; “The Taoism of the Western Imagination and the Taoism of China”/Russell Kirkland;“Tracing the Contours of Daoism in North America”/Louis Komjathy.

See also American Daoism, Dao, Daoism (Historical), Daoism (Normative), Daoism (Popular Construction), Philosophical Daoism, Popular Western Taoism, and the entries on Daoist.

Članek je povzet po ameriškem Center for Daoist Studies. Povezava do njega, kjer so aktivne tudi nadaljne povezave omenjene v članku, je tukaj.

Filed under: aktualni zapisi brez kategorije,zgodovina taijija,članki | Tagged: Dao,taiji |

Tale strip o taiji-ju se mi zdi fantastičen, vsaj po hitrem preletu…

Všeč mi jeVšeč mi je

Interesting piece of information, thank you.

Všeč mi jeVšeč mi je